Art by David Matlock (@empfindsamer)

You may be wondering: how do I decide what counts as the “best of the best” for each year?

I want to evaluate as many titles as humanly possible. So the first thing I do is some very in-depth research (five minutes on Google) in order to find all the titles which were released in the given year. Then I compile those into my own list, look up soundtracks, and listen to them all. Unless I can immediately tell it’s a stinker, I like to listen multiple times, take notes, watch playthroughs, and look up facts about the game’s development and its composer. All of this ends up being something we like to call “work,” and plenty of it.

As much as I want to be fair and give every title an equal shot regardless of notoriety or popularity, notoriety and popularity are still factors which contribute to the “greatness” of a piece of music. Some video games have been completely lost to time, and still more were technically discoverable but I just ran out of time on the search. It’s possible I leave great games off the list. Not likely, though. I’m confident I’m not unfairly leaving them off if no one’s ever heard of them. Am I so dedicated to being unpredictable or contrarian that I’m going to claim that the unknown titles were better than the ones that completely dominated the culture?

Is this whole introduction my excuse for why I’ve made the most obvious choice for the winner of 1985? Maybe. Yes. I also want to anticipate any comments, from both my fans, along the lines of “hey cool list but you forgot game X.” Besides being an extremely obnoxious comment, it’s also not true. I haven’t forgotten anything! I’m well aware your favorite might not be on the list, and that’s because I don’t think it should be on here. Hope this helps.

#8. Commando

Composer: Tamayo Kawamoto

Platform: Arcades

My original write-up spoke about the style of noise prevalent in arcades and so on. But then the OST of Commando got removed from YouTube and the account was scrubbed from existence and I can’t find anyone else posting it. Now this write-up is going to be a complaint about how corporations handle the rights to their older titles.

Oh, I’m very aware that OST uploads for retro games are almost unanimously unauthorized. The owners of that music (who are never the composers) are well within their rights to remove offending material. But where can you go to get access to the music without stepping on someone’s toes? Every rights holder for every retro game has plenty of opportunity to make it legal to listen to the OSTs, and every one of them willfully refuses to do so. It’s aggravating to see these corporations be just concerned enough about their works to punish anyone who breaks the slightest rule, but not concerned enough to make them accessible.

I don’t even remember what I was going to say about Commando. Fuck you. You can’t even listen to this soundtrack without going to a website where you must illegally download it. Whatever you do, don’t click the link and download these tracks, because that would be against the law.

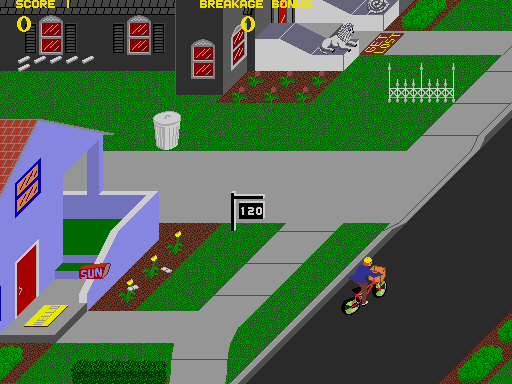

#7. Paperboy

Composer: Hal Canon, Earl Vickers

Platform: Arcades

Paperboy is the harrowing tale of a young boy conscripted into child labor, who must survive a neighborhood full of serial hit-and-run murderers, drunk drivers, sociopaths, and childnappers. The music has cowbell in it. Ah, the 80s.

As one of the earliest games with FM synthesis it stands out against most other arcade games because the sound samples resemble real instruments to some degree. You wouldn’t ever be fooled into thinking this is a real recording of acoustic instruments, but the style gives the impression that this is a live band playing alongside you. Paperboy also uses voice synthesis a lot. A lot lot. More than any other non-Laserdisc game up to this point. And it’s intelligible! Low bar to clear, but Paperboy does it effortlessly.

#6. Hang-On

Composer: Hiroshi Kawaguchi

Platform: Arcades

Despite racing games as a genre being around a decade old by 1985, there was always one thing missing: music playing while you drove. Enter Hang-On. There is only the one BGM track for the whole game, but that’s more than anyone else had.

Most other genres had already made the inclusion of BGM standard practice. Racing games were among the last for one very good reason: the abundance of sound effects. There’s the sound of the player car’s engine, the engines of the other cars, vehicle crashes, voiceover, ambient effects, and more. To fit in BGM, you would need to find another handful of spare sound channels on top of that, channels which are not being used by any of those sound effects.

Unfortunately, the BGM in Hang-On is mixed pretty low compared to the sound effects, so the best way to hear the tune is by just listening to the OST.

#5. Master of the Lamps

Composer: Russel Lieblich

Platform: PC (Commodore 64)

Sometimes Master of the Lamps is classified as a “music game,” but I’m not sure it really fits in the same genre that includes Rock Band or Guitar Hero. The core puzzle at the end of each level - if you can call what this game does “levels” - involves repeating a melodic line on a series of colorful gongs. Audio is certainly the principal element of that puzzle, but is it what the game is about? While we’re at it, what exactly is the game about? Whatever it is, MotL is experimental, and really pushes what the Commodore 64 is capable of.

Regardless of whether it’s accurate to call it a “music game,” MotL represents one of the earliest examples to treat its audio as an integral part of its development. Almost every other game at the time treated audio purely as an afterthought. Heck, even today most games still do this. It would be impossible to recreate any part of MotL without its music. It’s a game designed around the audio, and not a soundtrack written for an existing game.

#4. Dragon Buster

Composer: Yuriko Keino

Platform: Arcades

Pictured, how good Dragon Buster’s audio is.

Pictured, how good Dragon Buster’s Dragon Buster is.

And now, a reminder that this a list dedicated to finding the best game audio, and not the best overall games. Dragon Buster is... not good. The promotional poster is gorgeous, but the in-game graphics look bad, even for 1985. Even for an excuse plot this one is more excuse than plot. The gameplay loop gets old fast. Dragon Buster inspired a genre of games which would outmatch it in every way. But the music - the music is good. Not only that, it does something no other game had done yet.

This is the fourth time Yuriko Keino has appeared on this list. She is the one who invented the concept of a unified soundtrack, based on a single theme, with 1984’s Pac-Land. Now with Dragon Buster, she expands that concept, unifying the soundtrack around a single harmonic idea. Every level BGM in the game is built from the same pattern, with different melodies and waveforms. The chord progression always begins: C - Bb - Ab - G (all major chords).

Like with Pac-Land, this is a very simple version of that concept. But brand new concepts tend to start out simply. No one had done it yet. Keino invented this concept, just as she invented the melodic video game leitmotif and dynamic music.

Watch a playthrough of Dragon Buster

Listen to the Dragon Buster OST

#3. Gradius

Composer: Miki Higashino

Platform: Arcades

Hey, do you want to feel old? Miki Higashino, who composed the music for this game, was 17 when she wrote the soundtrack. What are you doing with your life exactly?

Gradius belongs to the “Shoot-Em-Up” genre, or “Shmups” as all the cool kids are saying. It wasn’t the first of that genre, not by a long shot. Space Invaders might have been the originator. For some reason the earliest shmups were always spaceships and aliens, though there’s no law that the genre had to be set in outer space. But given their nature, shmups tended to be very noisy. That meant no BGM until the tech allowed for a greater number of sound channels.

Usually when a genre adds music for the first time, it does so in baby steps (such as Hang-On’s single BGM track). Not so with Gradius, which has a unique track for each level. On top of that, there is one additional track that plays at the start of every new level. No other contemporary arcade game of any genre did as much as this, especially not while having such popular and catchy tunes. I’m always partial to level one’s theme, simply because I was never good enough at the game to get to level two.

#2. Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar

Composer: Ken Arnold

Platform: PC (Apple II, Commodore 64, IBM PC, and more)

I don’t think it’s possible to overstate the place Ultima IV holds in the RPG genre, and gaming as a whole. For those of us born too late, the Ultima games were a series of RPGs in the 80s and 90s which practically invented the video game RPG, and in particular, the “Western*” RPG. (There were some other RPG series which were also foundational, but none quite reaches the level of Ultima.) In comparison to modern RPGs, they are dated and primitive. But every Western RPG all the way up to Fallout and Skyrim owes its origins to Origin Systems. And of all the Ultima games, Ultima IV was the most innovative and formative to the entire genre. I’ll spare you the details now but you should definitely check this game out when you get a chance.

Here’s a small list of the things the soundtrack of Ultima IV established, if not originated:

General conventions of music for Western RPGs such as the standard style and structure of tunes. You know, vaguely medieval and Celtic folk as opposed to 80s metal or pop (such as you’d hear in 80s fantasy films like Lady Hawke).

The notion that a video game soundtrack should consist of multiple different tracks with a decent amount of variety, and not all based on one feel or tune.

Making a game’s soundtrack inseparable from the game itself, so that you shouldn’t (or couldn’t) play the game without the music.

Keeping music consistent between all ports of a game, being composed by the same person.

Reprising a melody from a previous game, establishing themes that apply to a whole series instead of a single entry.

So, there’s a lot of ports for Ultima IV and thus multiple versions of the soundtrack, based on the audio hardware for each computer. I prefer the original Apple II version, played on the Mockingboard, and so that’s what I’ll link. If you like a different version, you can look those up on your own time. The main reason I prefer the Apple II version is that the peripheral Mockingboard add-ons could stack. Each board gave three sound channels, so if you put two boards on, you got six. The other ports were locked to three or four channels, depending on the hardware. So, the original version has a few tracks that use all six voices, leading to some nice crunchy harmonies that I really love.

This is a huge RPG and there’s no way you’re going to get it all in one session, but here’s a link to the start of a longplay.

Or, here’s the OST in the original Apple II version if you don’t want all the static.

#1: Super Mario Bros.

Composer: Koji Kondo

Platform: Console (NES)

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who know the Mario Bros. theme song, and liars who are going to Hell.

I would love to ignore Super Mario Bros. or find a reason to drop it a spot. What a high I could get by saying “Mario isn’t good, actually.” But come on. There’s no way I’m not giving 1985 to Super Mario Bros. The main theme from this game has permeated pop culture so completely that even people who have never played any video games recognize it.

The soundtrack is rather short, like most OSTs of the era, and I want to shout out three of the four level BGM tracks individually, in a long and boring fashion.

The overworld theme: So, the NES had five sound channels total. The first two were pulse wave channels (which could vary a little in waveform), the third was restricted to the triangle wave, and the fourth was a white noise channel only. As for the fifth, it was where the NES could play PCM samples, but it was rarely used, especially before 1988. Anyway, if you’re keeping score at home, that means there are only three channels which play notes. Most chords are at least three notes. Do the math. If you wanted to write a tune that had a melody and chords, you had to get very creative. What Kondo does here is a style of voice leading not heard much before in any kind of music, let alone video game music: he composes the main theme of chords so that all three notes are always present and the top note is always the melody note. This is especially impressive given how much the melody jumps around in large intervals.

The underworld theme: You probably know this one, too. However, you might recognize it from later Mario titles which reuse it. And in all those later titles, the music is actually a little different. For example, the first ever reprise of this tune, from Super Mario Bros. 3, adds a drumbeat which forces the entire track into eight bars of 4/4. That’s not how it was originally conceived. This tune is seven bars of 3/4 time, which makes the downbeat harder to find and keeps the track unpredictable.

The underwater theme: Okay, let’s talk song structure. Often we identify themes with letters, dividing songs up into an A theme, B theme, and so on for however many themes there are. A common structure is called “32-bar song form,” written as AABA. “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” is a classic AABA format. So is “Sixteen Going on Seventeen.” (This structure was especially popular in the middle part of the 1900s.) Something that Kondo likes to do, and which would become standard in classic video game music, is to structure a tune so that it sounds like it’s following the AABA pattern, but just drops the final A section, instead extending the B section to wrap up the tune. It’s AAB. This is the kind of thing that interests me. This is what I spend my time looking at instead of going outside.

So I don’t care how predictable it is to put this game at the top of the list. There’s no way you could look at any other soundtrack from 1985 and disagree.

Do you really need to see this game? Ok.

In case you’ve never heard this OST

* There’s a whole thing about the difference between “Western” RPGs and “Japanese” RPGs (which are known as JRPGs). It’s not just that they are manufactured in different parts of the world, but the design philosophy tends to be different. I’m separating the ideas so long as it has any meaning to readers. I’m well aware there’s lots of arguing as to what really makes an RPG one or the other, or whether it’s demeaning to the genre to use such terms. As is usual in these cases, I don’t care and you’re all annoying. Have a good one.